All of us interested in improvising in the jazz idiom need mental tools of simplifying jazz harmony. The concept I would like to discuss in this article, which I think can help in understanding harmony and chord substitutions, is that of the three diminished families. But before we examine the three diminished families let me put our discussion into context.

All of us interested in improvising in the jazz idiom need mental tools of simplifying jazz harmony. The concept I would like to discuss in this article, which I think can help in understanding harmony and chord substitutions, is that of the three diminished families. But before we examine the three diminished families let me put our discussion into context.

DOWNLOAD THE PDF OF THIS POST

When we zoom out of western harmony we can generally detect 2 areas: The area of harmonic tension and the area of harmonic release. Generally speaking, harmonic tension is represented by dominant chords very often joined by minor 7th chords (Gm7-C7, Gm7b5-C7#9,) while harmonic release is represented by major 7th or 6th type chords (Cmaj7, Cmmaj7 Cm6,).

Jazz musicians have enjoyed using the diminished sound as a substitute for the dominant 7th chords (tension areas) due to its property of carrying the necessary amount of inherent tension. The 2 tritone intervals that exist in the diminished arpeggio represent the backbone of harmonic tension in our western tonal harmony system and constitute a powerful tool in improvisation.

It’s worth noticing that the minor third interval -the basic building block of the diminished sound- fails to convey the major sound quality which is defined by a major third interval. However, the diminished sound can be used effectively in order to lead into major chords, implying the 5 of a major chord. This creates nice movement in our lines, an idea jazz guitarist Joe Pass discusses in his 1991 ‘Jazz Lines’ video lesson.

So, the diminished sound can satisfactorily convey the minor and dominant sound qualities and that’s why it is very often used on the 2-5 area of a 2-5-1 progression.

Here is the idea:

1st DIMINISHED FAMILY

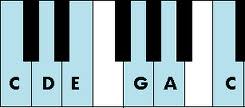

The first diminished family is defined by the diminished arpeggio:

G, Bb, C#, E (Tritones: G-C# and Bb-E)

And the equivalent diminished scale which is basically formed by chromatically approaching each of the diminished arpeggio notes:

F#-

G-A-

Bb-C-

C#-Eb-

E

The diminished arpeggio and the equivalent diminished scale relate with these minor chords:

Gm, Bbm, C#m, Em

We can convey these minor chord qualities satisfactorily by playing the above diminished arpeggio from the root of these chords. When we do that we provide the root, the minor third, the flat 5th and the 6th (all of them nice and valid)

The diminished arpeggio and the equivalent diminished scale also relate with these dominant chords:

C7, Εb7, F#7, A7

We can convey these dominant chord qualities by playing that same diminished arpeggio one half step above the root of these chords. When we do that we provide the flat 9, the major third, the fifth and the flat 7 of every chord (all of them nice and valid).

So, no wonder we come across these 2-5 progressions in jazz:

Gm7 C7

Bbm7 Eb7

C#m7 F#7

Em7 A7

See these 5-1s as belonging to the same family. When we conceptualize these 5-1s as a family we can immediately see why substituting Bbm7-Eb7 for Gm7-C7 works (jazz theorists call this backdoor substitution-the idea of using a 2-5 a minor third above your original 5-1) and why substituting C#m7-F#7 for Gm7-C7 also works (the famous tritone substitution-the idea of using a 2-5 a tritone away from your original 5-1).

The point is that we can convey the harmony of these 2-5s just by using the four notes of the same diminished arpeggio. This is a great starting point for improvising. Try to apply rhythmic patterns on just these four notes and I am sure you’ll see the interesting ideas you can come up with. If we now choose to use the equivalent scale then we skyrocket our potential, since a treasure of melodic material lies within the diminished scale. Check this yourself on your instrument.

If we approach the tension areas of a new tune using this approach we narrow our choices of melodic material on harmonic tension areas down to three. And this is true not only for strictly diminished lines. Take the popular Cry Me a River lick, a melodic fragment that all great jazz players have incorporated into their playing:

Strictly speaking you wouldn’t call this a diminished line right? But the last 3 notes of the phrase do belong to the diminished scale of our first Diminished Family, so you could actually treat it as melodic material belonging to the first diminished family, as the G minor chord also indicates. Of course, you can expand this idea further by organizing melodic ideas you already know based on their resemblance to one of the three diminished families.

Jazz saxophonist Michael Brecker was a master of the diminished tool. If we master the diminished concept and go beyond than just going up and down the scale, not even experienced ears will be able to understand our mental source of improvisational ideas. Thinking diminished does not necessarily mean sounding diminished! What we are doing is setting up a mental framework.

So, here are the other two Diminished families:

2nd DIMINISHED FAMILY

The second diminished family is defined by the diminished arpeggio:

Ab, B, D, F (Tritones: G#-D and B-F)

And the equivalent diminished scale:

G-

Ab-Bb-

B-C#-

D-E-

F

The diminished arpeggio and the equivalent diminished scale relate with these minor chords:

Abm, Bm, Dm, Fm

…and these dominant chords:

Db7, E7, G7, Bb7

And these are the 2-5 progressions that are formed:

Abm7 Db7

Bm7 E7

Dm7 G7

Fm7 Bb7

3rd DIMINISHED FAMILY

The third diminished family is defined by the diminished arpeggio:

A, C, Eb, F# (Tritones: A-Eb and C-F#)

And the equivalent diminished scale:

G#-

A-B-

C-D-

Eb-F-

F#

The diminished arpeggio and the equivalent diminished scale relate with these minor chords:

Am, Cm, Ebm, F#m

…and these dominant chords:

D7, F7, Ab7, B7

And these are the 2-5 progressions that are formed:

Am7 D7

Cm7 F7

Ebm7 Ab7

Fm#7 B7

Remember that this is just one mental tool of simplification. There are other great tools like visualization, especially interesting for us fiddlers since our in instruments are symmetrically tuned in fifths. We will discuss the power of visualization in another article.

Don’t neglect to play back up tracks when experimenting. Good luck and let me know what you think!

If you found this post helpful and inspiring, the smallest contribution will encourage the author to continue writing and sharing his ideas.

Thank you!

Watch this woman in the photo holding a lifestyle magazine while she is kicking a girl playing her accordion for a few euros. Apparently she did not like this girl being near her shop. (This photo was taken just under the Acropolis in Athens earlier this year by Associated Press photographer Dimitris Messinis). The scene is exasperating but it also stands as direct evidence of my point that just the image of a little girl playing music led this woman to manifest herself in a certain way, whereas otherwise she would pass as a good mannered middle class shopkeeper. The social value of busking lies exactly in this: It can touch upon issues of freedom, cultural appreciation and co-existence.

Above all, when we busk we are building an example of unmediated social relations with our listeners. In the street you can be pretty sure that when people appear thankful and express their gratitude, they most likely mean it. By the same token, the reaction of the shopkeeper, who came up to us complaining for the noise we were making, rightfully belongs to the wide spectrum of possible feedback we should expect. I truly welcome these remarks not because I trust everyone’s musical criteria but because I feel that they help me stay in touch with a reality that -fairly or unfairly- often devalues artistic attempt and creation. Hiding in a jazz bar with jazz fans is not the real picture, although I certainly understand the need for it.

I have described the ritual of busking as a healthy social context -and I believe it is definitely healthier than the sterilized streets people walk up and down every day going to work and all the other rituals we participate in, like job interviews or even concert hall performances. In my mind that’s why children feel so comfortable being around it, and that’s why they naturally end up being the best and most devoted listeners of all. Busking is just great for children. It is fun, lively and provides a world of visual and auditory stimuli just like the ones children are so thirsty for. Watch the excitement of this child while we were busking on the island of Antiparos last summer.

I have had a great time busking, I have met great people while doing it and I encourage all musicians to give it a try.

Watch this woman in the photo holding a lifestyle magazine while she is kicking a girl playing her accordion for a few euros. Apparently she did not like this girl being near her shop. (This photo was taken just under the Acropolis in Athens earlier this year by Associated Press photographer Dimitris Messinis). The scene is exasperating but it also stands as direct evidence of my point that just the image of a little girl playing music led this woman to manifest herself in a certain way, whereas otherwise she would pass as a good mannered middle class shopkeeper. The social value of busking lies exactly in this: It can touch upon issues of freedom, cultural appreciation and co-existence.

Above all, when we busk we are building an example of unmediated social relations with our listeners. In the street you can be pretty sure that when people appear thankful and express their gratitude, they most likely mean it. By the same token, the reaction of the shopkeeper, who came up to us complaining for the noise we were making, rightfully belongs to the wide spectrum of possible feedback we should expect. I truly welcome these remarks not because I trust everyone’s musical criteria but because I feel that they help me stay in touch with a reality that -fairly or unfairly- often devalues artistic attempt and creation. Hiding in a jazz bar with jazz fans is not the real picture, although I certainly understand the need for it.

I have described the ritual of busking as a healthy social context -and I believe it is definitely healthier than the sterilized streets people walk up and down every day going to work and all the other rituals we participate in, like job interviews or even concert hall performances. In my mind that’s why children feel so comfortable being around it, and that’s why they naturally end up being the best and most devoted listeners of all. Busking is just great for children. It is fun, lively and provides a world of visual and auditory stimuli just like the ones children are so thirsty for. Watch the excitement of this child while we were busking on the island of Antiparos last summer.

I have had a great time busking, I have met great people while doing it and I encourage all musicians to give it a try.